Modules

Here we list the various modules in our yalnix implementation… each module has its own header file, and a well-defined API.

kernel

The kernel module stores all code necessary for booting yalnix, and other necessary procedures.

The two important functions are KernelStart and SetKernelBrk.

KernelStart initializes all important kernel data structures and initializes virtual memory for the system.

SetKernelBrk is called each time the kernel must resize its heap, and allocates free frames accordingly.

kernel_utils

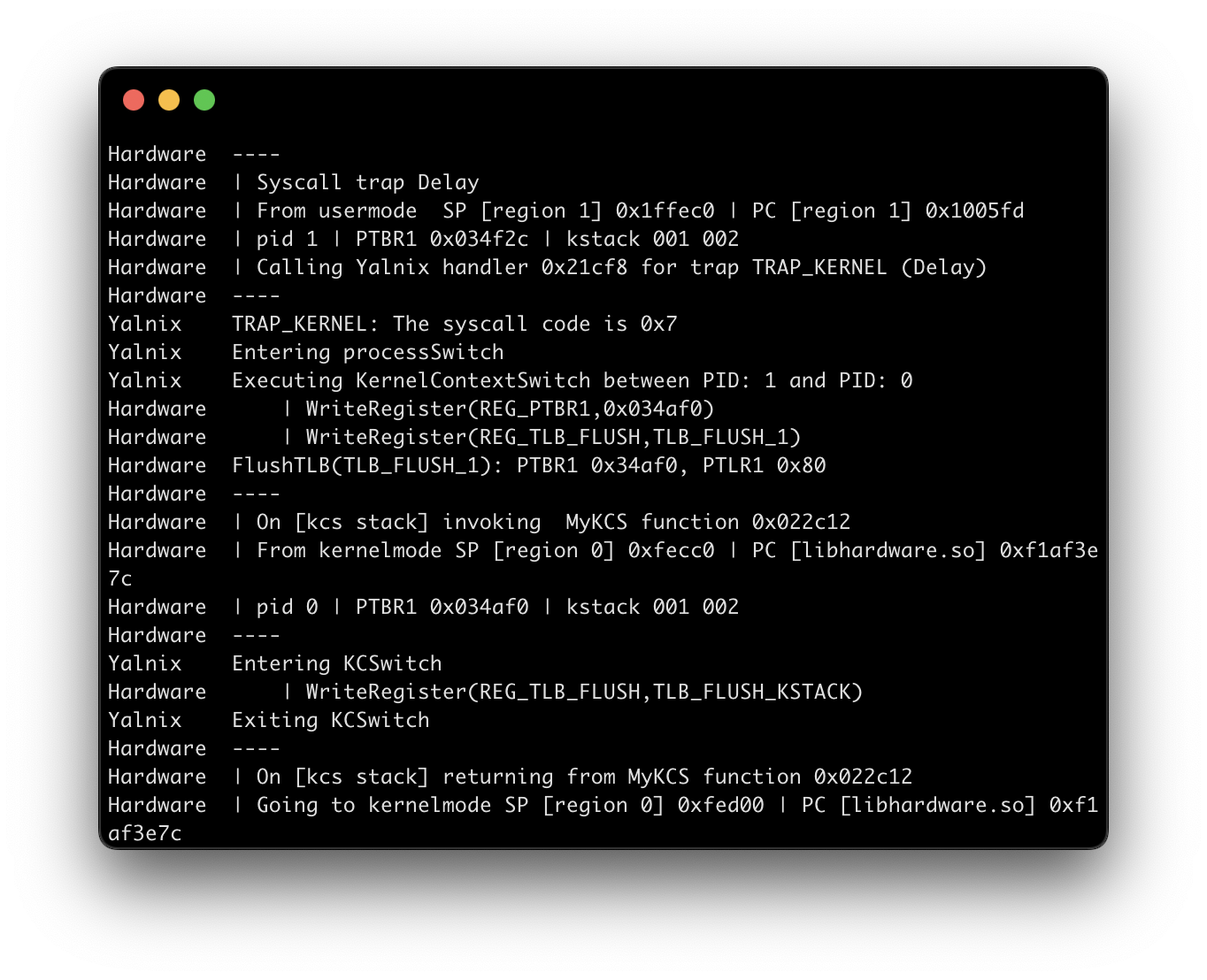

The kernel_utils module provides methods to print the user context, the doIdle function, KernelContext switching and copying.

It also has a heap checker which we used in debugging, as well as yalnix_xalloc, for memory allocation checkers that would TracePrint and abort if there was an issue allocating memory in the kernel.

We also have helper functions to check if an address is in region 1 and if it is readable/writeable by the user, which is used for checking buffer addresses for syscalls.

pagetable

The pagetable module stores all functions and routines involving pagetables and pagetable entries (PTEs).

The module abstracts all access away from accessing raw PTE elements, so allows writing safer code throughout the program.

bitvector

The bitvector module allows for an abstract representation for tracking free memory frames.

Each free frame of memory is represented by a ‘0’ on the bitvector and a ‘1’ means that the frame is mapped to virtual memory.

For the machines that we used, there were typically 512 frames of physical memory available, but the size of the bitvector is dynamically determined by bootstrapping inside KernelStart

linked_list

The linked_list module is an implementation of a linked list data structure and is used throughout Yalnix for creating queues and other lists.

It provides several queue-specific functions such as dequeue and peek and is generally used as a FIFO list.

We wrapped linked list functions in all other list/queue function calls in other modules so that there was less repetition of code throughout the project, and so that it was easier to isolate bugs to one module.

pcb

The pcb module implements the process control block data structure used in our kernel.

We initially wrote it to have be its own linked list node, but because we want to keep a linked list of children we decided that each pcb should be its own structure that has pcb_node types pointing to it (so we also implement wrapper functions / structures for pcb_lists off of the linked_list module).

The pcb_t struct is transparent to the user, but it also has methods for dealing with pcb lists, dealing with the process’s child list, creating new and retiring processes, and getting processes from queues.

prog_mgmt

The proc_mgmt module contains methods and global structures for process management.

The currently running process and process queues are global variables from this module, as well as methods to initialize the Idle and Init PCBs.

It also has methods to help with sleeping processes and switching processes.

We implemented our round-robin scheduling algorithm in this module, in which the kernel will switch to the first process off the ready queue (or go to idle if there are no processes ready).

We also have methods for blocking the current process and unblocking the process (which takes in a flag for if it’s in the blocked queue or stored in another bookkeeping structure, like a pipe, cvar, lock, etc.).

LoadProgram

This module allows for programs specifically compiled for Yalnix to be loaded into kernel memory. The backbone for this module was mostly written for us, but we added specific implementation details such as how we handled pagetables and bookkeeping for PCBs.

trap

The trap module implements the traps the hardware can throw to Yalnix.

trap_clockwill decrement the timer on sleeping processes, and then perform a round-robin process switch if there are any ready processes.trap_kernelwill, through a switch case, call the syscalls described in thesyscallsmodule.trap_memorywill handle access errors and map errors. In the case of an access error, the process will be killed, and in the case of a map error, if the offending address is below the stack and above the red zone, the stack will grow to meet it, otherwise the process will be killed.trap_illegalwill kill the current process (user error)trap_mathwill kill the current process (user error)trap_tty_transmitwill unblock the process that is waiting on a given TTY terminal to finish transmitting.trap_tty_receivewill receive the bytes from a tty input into the tty buffer (described inttymodule) and unblock the process currently waiting to receive input from that terminal (if there is one). If there are more bytes to receive than there is space in the receiving buffer, the buffer will double in size until there is space. (So the tty terminal could fill up the kernel memory if there are enough inputs into the buffer that are not read or flushed by a program).trap_unimplementedwill TracePrint at level 1 if the interrupt vector table somehow throws a trap that we can’t handle.

syscalls

The syscalls module contains code to handle each of the 21 Yalnix syscalls on the kernel end of the OS.

Each time a user program calls a syscall, the hardware throws a TRAP_KERNEL and executes one of the syscalls according to the UserContext provided, will call the appropriate kernel syscall handler.

Syscalls return integer return codes like -1 for ERROR and 0 for success, but also integer values when reading from / writing to buffers, described in the modules that contain our syscall logic below.

tty

The tty module describes structures and functions for handling tty input and output.

There are buffers for tty output (tty_buf) and for input (tty_recv_buf).

They both hold a pointer to an allocated buffer, a pointer to the end of the data in the buffer, and the length of the data in the buffer.

Additionally, tty_recv_buf holds the size of the allocated buffer so that it can grow if necessary.

There are also global arrays of pcbs and buffers for each tty_terminal (send and receive).

There’s a tty_init method that KernelStart calls to initialize all the global arrays.

When a user calls TtyWrite, the kernel (after trapping and calling the syscall) will allocate a buffer in the kernel, copy the data from the user buffer into the kernel buffer, and then write the maximum number of bytes to the tty terminal until the entire kernel buffer is finished (blocking each time and waiting for the trap_tty_transmit to unblock it), and then the number of bytes written in total will be returned.

When a user calls TtyRead, the process will check to see if there are any bytes available in the kernel buffer (and block if there are not, waiting for the trap_tty_receive to unblock it), and then copy either the requested number of bytes or the number of available bytes from the kernel buffer into the user buffer, whichever is lesser, and return that number in the syscall.

If the user reads fewer bytes than there are in the buffer, the kernel will shift the buffer to move the next-available bytes to the front of the buffer.

We also handle a number of bad / malicious inputs by returning -1 (defined ERROR) from the syscalls.

If the TTY_id’s are bad, we return -1.

If the buffer length is a negative integer, we return -1.

If the user tries to pass in a buffer that is not in region 1, we return -1.

TtyWrite is allowed to read from any buffers in user memory that are valid (including user text), because the user should be allowed to read their own text.

However, TtyRead is not allowed to write tty input into buffers in user memory because the user should not be allowed to overwrite their own code.

We also put a hard cap on how many bytes a buffer can be (in both tty and in pipe) of 0x4000 (defined in include/kernel.h), because we felt that there should be protection in the kernel from a user trying to allocate too big of a buffer for a pipe or tty_terminal.

If a user tries to TtyRead or TtyWrite more than 0x4000 bytes in one go, they will get a return code of -1 (and no bytes will be written/read).

If a user, through their keyboard / tty input, tries to input enough bytes such that the tty buffer will overflow to be more than 0x4000 bytes, it will stop saving bytes once the size is more than 0x4000.

All of this behavior is tested in the test/tty_break.c described in the TESTING_README.md file, with the expectation of this final tty input overflow issue, because we were unable to test reading in so many bytes into the tty terminal using the -In <filename> argument.

Replicate this by running ./yalnix -lk 3 -I0 test.in -x -W test/ttybreak_serious after creating a file test.in in your directory with more than 17kB of garbage data and see that the kernel aborts because the tty process aborts before our kernel can handle the input.

pipe

The pipe module contains all data structures and functions necessary for Yalnix’s three IPC syscalls.

Our implementation of pipes are doubly ended, meaning that if a process has a pipe, it can both write and read from it.

Pipes are implemented in a similar way as TTY, meaning that the pipe data structures contain a pointer to a dynamically allocated buffer, a pointer to the start of the buffer (which is typically the same as the buffer except temporarily when reading from the pipe).

There is also an integer that is the pipe ID and a pointer to a list of PCBs that might be waiting on that pipe.

The user must call PipeInit on a pointer to an integer to assign that integer to the correct PipeID (which will always be a multiple of 3, for handling the Reclaim syscall that needs to differentiate pipe, cvar, and lock IDs) and will return 0 for SUCCESS and -1 for ERROR (errors cases described below).

A user can write data to the pipe with PipeWrite, which will write the given length of bytes to the kernel buffer from the user buffer, and then return the length written (or ERROR if there is an error growing the pipe buffer, such as if it is more than the max buffer size defined in include/kernel.h, and then it will broadcast to any processes waiting on the pipe to wake up to try to read.

A user can read data from the pipe with PipeRead, where it will block if there are no bytes to read (and add to a list of waiting processes), or copy the given or available number (whichever is less) from the kernel buffer to the user buffer, returning that length or ERROR if there are any errors (described below).

We also handle a number of bad / malicious inputs by returning -1 (defined ERROR) from the syscalls.

If the PipeIDs are bad, we return -1.

If the buffer length is a negative integer, we return -1.

If the user tries to pass in a buffer that is not in region 1, we return -1.

PipeWrite is allowed to read from any buffers in user memory that are valid (including user text), because the user should be allowed to read their own text.

However, PipeRead is not allowed to write from the kernel pipe buffer into buffers in user memory because the user should not be allowed to overwrite their own code.

We also put a hard cap on how many bytes a buffer can be (in both tty and in pipe) of 0x4000 (defined in include/kernel.h), because we felt that there should be protection in the kernel from a user trying to allocate too big of a buffer for a pipe or tty_terminal.

If a user tries to PipeWrite more than 0x4000 bytes in one go, they will get a return code of -1 (and no bytes will be written/read).

If a user tries to PipeWrite less than 0x4000 bytes but it will cause the pipe buffer to grow to be more than 0x4000 bytes, it will write the bytes that get it to be right at the max size and return that number of bytes, unless the buffer is exactly full, in which case it will return -1.

All of this behavior is tested in the test/pipe_break.c described in the TESTING_README.md file.

sync_vars

The sync_vars module contains functions and data structures for all of the synchronization syscalls in Yalnix.

There are both mutexes (lock_t) and conditional variable (cvar_t) data structures implemented in the module.

The module also maintains a list of all locks and conditional variables stored in the kernel, and marks them each with a unique ID.

We specifically implemented unique IDs between pipes, cvars, and locks based on the fact that we know there only need be three global lists, one for each data structure.

Thus, each pipe has an id where pipe_id % 3 = 0, lock has an id where lock_id % 3 = 1, and cvar_id % 3 = 2.

We made the specific implementation choice that if a process dies or is killed while holding a lock, it will release said lock.

Also we made the design choice that a lock can only be reclaimed by a user program if it is not currently held by any process.

Specific Design Choices for Sync Vars

lock_id % 3 = 1andcvar_id % 3 = 2(andpipe_id % 3 = 0) because we wantedReclaimto be able to tell apart the different IDs when trying to callpipe_delete, etc., so this felt like a solution with the least overhead to be sure that lock, cvar, and pipe IDs are all exclusive.- Processes release locks upon death to prevent deadlocks. Furthermore, if a process is queued to acquire the lock but then dies before acquiring it, it is skipped over in the queue for an alive process.

- Locks can only be reclaimed if they are currently unheld by a process.